The foothills of the Yatsugatake mountains were once a central hub of the Jomon culture. This time, I want to embark on a journey to experience the ancient beliefs and way of life in Japan.

Day1

Mossy Forests and Primeval Woods

Why was this area the center of Jomon culture? It’s said to be because of obsidian. The northern Yatsugatake region has a high concentration of veins where good quality obsidian can be found. I began by walking through these northern Yatsugatake forests, primarily composed of conifers like spruce and fir.

Unfortunately, it was raining that day, but the moss was vibrantly alive. This area is known as a “mossy forest” and is home to over 500 types of moss. The moss-covered forest brought to mind the forest from “Princess Mononoke.”

After a short walk, I came to a pond over 2,100 meters above sea level. Around the pond, there are mountain huts and campsites where you can stay. There are also hiking trails to the surrounding mountains. As the rain got heavier, I gave up on climbing and headed for a museum where many Jomon pottery and dogu (clay figurines) are displayed. By the way, this area also has many high-altitude wetlands, which are great for summer hiking.

Chino City Togariishi Jomon Archeological Museum

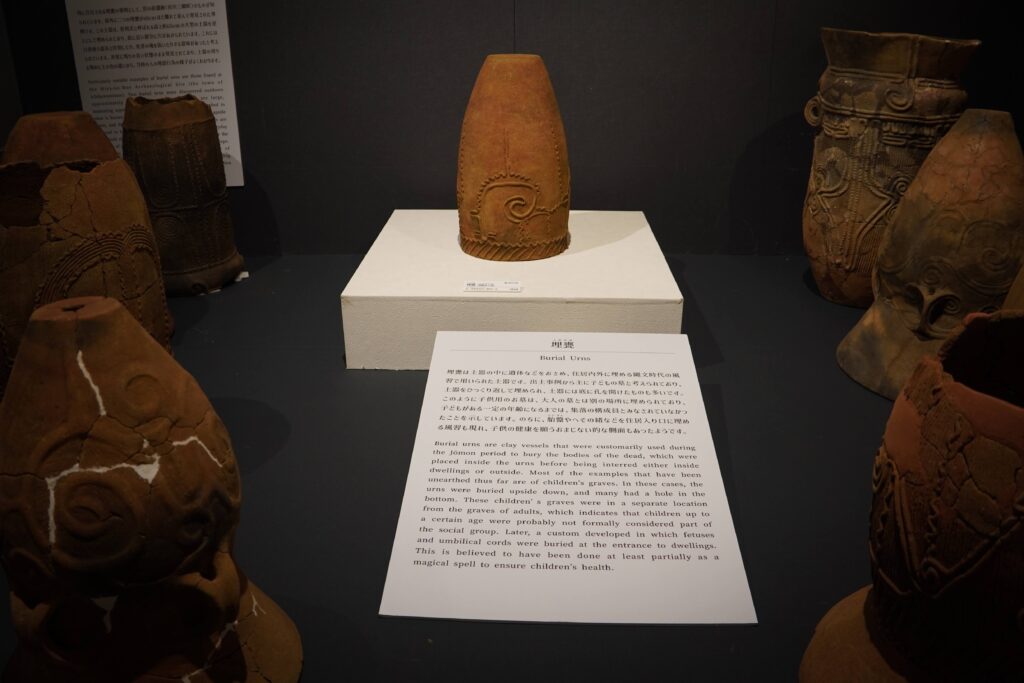

About a 30-minute drive down the mountain from the forest entrance, I arrived at the Chino City Togariishi Jomon Archeological Museum. The main attractions are the “Jomon Venus” and the “Masked Goddess,” which are national treasures, but many other well-preserved Jomon pottery pieces are also on display. You can also learn about life, culture, and trade during the Jomon period.

During the Yayoi period, which focused on rice cultivation, pottery was relatively simple. In the Jomon period pottery was decorated with various patterns. These decorations are said to express stories or objects of faith. While various creatures are depicted, snakes were particularly common. Since snakes repeatedly shed their skin, they might have been a symbol of “life force,” representing eternal life or rebirth. The beliefs of Suwa Grand Shrine, which I’ll visit next, are also connected to snakes.

Suwa Grand Shrine

I got so absorbed in the museum that it was already evening, but I headed to the Suwa Grand Shrine Kamisha (Upper Shrine), about a 30-minute drive away. Suwa Grand Shrine consists of four shrines built and enshrined around Lake Suwa. Every seven years, a famous ritual called the “Onbashira Festival” takes place. It’s a spectacular festival where large trees are cut down in the mountains, and people ride them down slopes and across rivers. The large trees transported in this way are then erected at the four corners of each Suwa Grand Shrine.

Here, I’d like to tell you a little about Takeminakata, who is considered the main deity of Suwa Grand Shrine, and the Kuniyuzuri (Transfer of the Land) story from the Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters). There are many characters, so feel free to skip if it’s hard to follow.

Story Of Kuniyuzuri

The general flow is a story where the ancestors of the current Imperial Family, the lineage of Amaterasu Omikami from Takamagahara (High Plain of Heaven), descend to the earthly realm governed by Okuninushi of the Izumo clan and demand the transfer of the land. They send envoys several times, but they are refused, and things don't go well. So, they dispatch very strong warrior gods: Takemikazuchi, who is considered the god of thunder, and Futsunushi, the god of swords, to demand the transfer of the land.

Okuninushi leaves the decision to his sons, Kotoshironushi and Takeminakata. Kotoshironushi immediately agrees, but Takeminakata, who excels in martial prowess, is not convinced and engages in a test of strength with Takemikazuchi. However, even the strong Takeminakata can't beat thunder and loses, fleeing. Takemikazuchi chases him and finally reaches the land of Suwa. Here, Takeminakata gives up and surrenders, swearing that he will never leave this land again, and settles in Suwa. It is said that he then built a new country in Suwa and was enshrined at Suwa Grand Shrine. Incidentally, this test of strength between Take-minakata and Takemikazuchi is said to be one of the origins of sumo wrestling.

As an aside, in Japan, the 10th month of the lunar calendar is called "Kannazuki" (Month without Gods). This means it's the month when gods leave their respective shrines. This comes from the belief that the gods enshrined in each shrine gather in Izumo for a meeting. Izumo was the center of the Nakatsu Kuni (Central Land) governed by Okuninushi, and it's where Izumo Grand Shrine, where Okuninushi is enshrined, is located. In Izumo, contrary to other regions, the 10th month of the lunar calendar is called "Kamiarizuki" (Month with Gods). And since Takeminakata swore not to leave Suwa, he doesn't participate in the meeting, so the Suwa region does not experience Kannazuki.

Arrival at Suwa Grand Shrine Kamisha

I arrived at Suwa Grand Shrine in the evening. It was getting dark, and there were almost no people around, creating a solemn atmosphere. As I passed through the torii gate from the north approach, the first pillar erected caught my eye.

Normally, after passing through a torii, the main hall (haiden) would be directly in front, but here, it’s to the left after climbing some stairs. The object of worship directly in front is the mountain itself. It seems there’s another mystery here. The four pillars were erected near the north approach, the east approach, and within the forest. Considering the Kuniyuzuri story from the Kojiki, these four pillars appear to me as if they are sealing Takeminakata.

Wind chimes were hanging in the corridor, as is typical for summer, and the lanterns were lit, creating a wonderful atmosphere. Many large zelkova trees stood within the shrine grounds. Tomorrow, I plan to visit the former residence of the Moriya family, who served as priests of Suwa Grand Shrine for generations, and the remaining three Suwa Grand Shrines.

Day2

The second day was clear, contrary to the forecast. First, I headed to Suwa Grand Shrine Maemiya, the “Former Shrine” of the Upper Shrine complex.

Kamisha Maemiya

Maemiya is considered the oldest among the four Suwa Grand Shrines and is said to be the birthplace of Suwa faith. Suwa Grand Shrine Kamisha (Upper Shrine) has a unique priestly position called Ohohri (大祝). The Ohohri served as the living deity (arahitogami) of Suwa Myojin, standing at the pinnacle of both the Upper and Lower Suwa Shrines. Maemiya is where the Ohohri first established their residence.

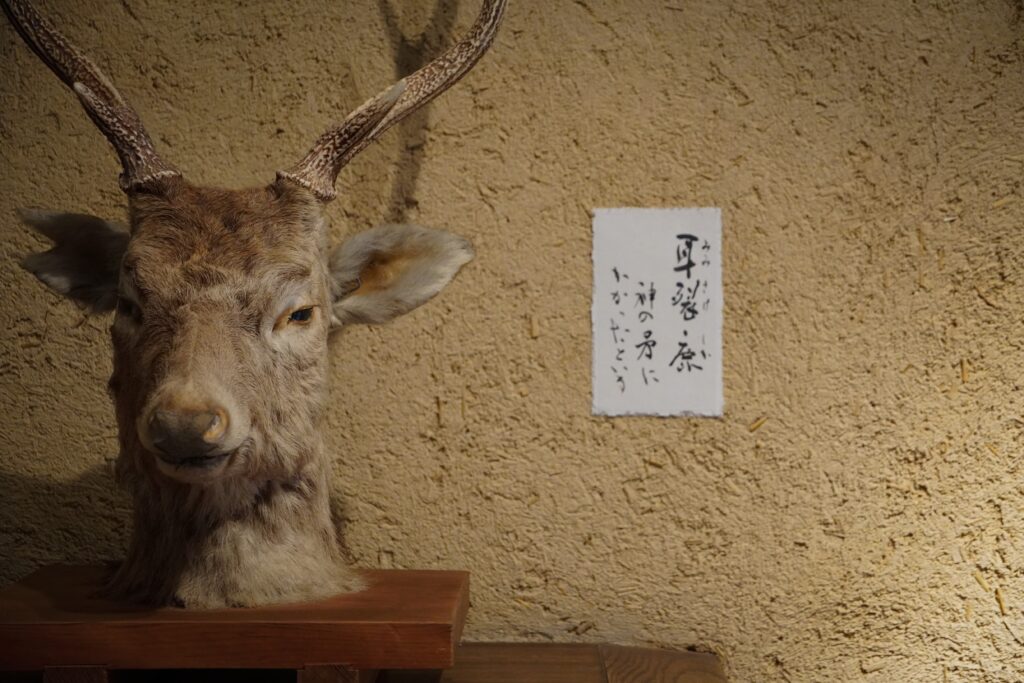

Upon entering the grounds, I saw a building called Jikken-ro on the left. This is said to be where the Ohohri performed sacred rituals. It is also the site of an important ritual called the Ontosai (御頭祭), which involves offering 75 deer heads to the deity. (Currently, stuffed deer heads are used.) This ritual evokes primitive hunting ceremonies, hinting at an aspect of the deity as a god of hunting and revealing ancient connections. I hope to attend the Ontosai myself someday and report on it if I get the chance.

Beyond Jikken-ro, climbing the stairs led me to the main hall, nestled among trees on a slope. Behind it lies Mount Moriya, considered the sacred body of the deity, and spring water flows from the mountain, making it a pleasant place. And here too, of course, the main hall is surrounded by four Onbashira pillars. You can walk around the main hall, allowing a close look at all four pillars.

A Shinto priest happened to be performing prayers. After completing prayers inside the main hall, they continued to offer prayers outside. I asked a regular visitor who happened to be there, and they told me that the mother of Take-minakata is enshrined in a corner outside the main hall. Take-minakata’s mother is said to be a princess from Niigata, famous for its jade production, and it’s believed that jade was used in her rituals. This also suggests ancient regional exchanges through jade and obsidian.

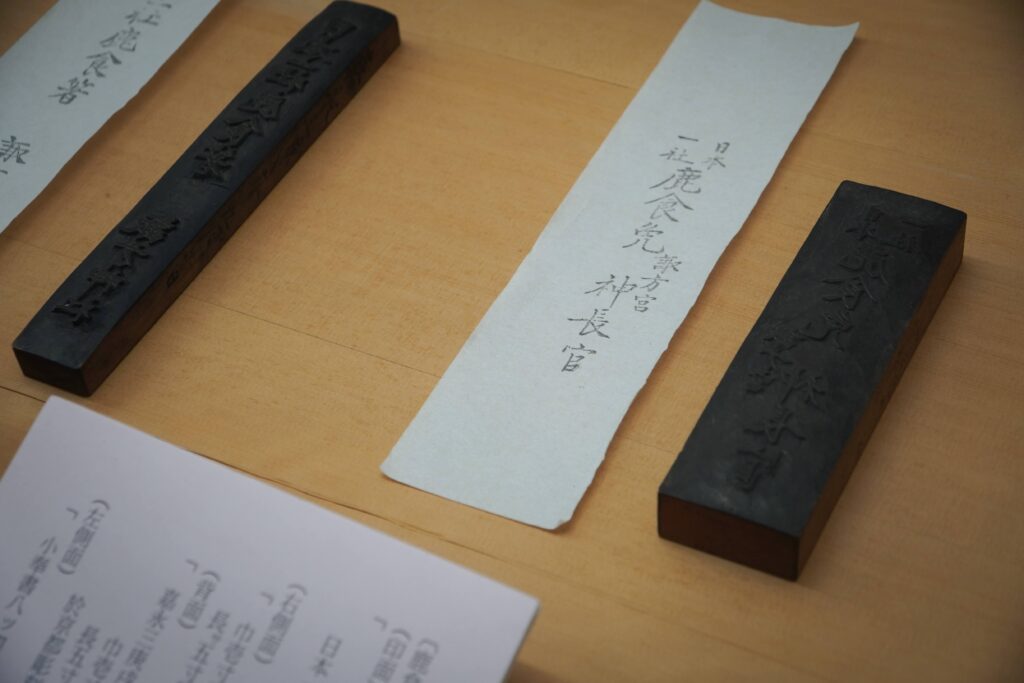

Priest Moriya

Next, I visited the museum and shrine on the grounds of the Moriya family residence, who have served as the chief priests of Suwa Grand Shrine for generations. The Moriya clan is said to have governed this land before Take-minakata arrived in Suwa. According to local legends, Take-minakata fought with the Moriya clan’s ancestor, Moriya-no-kami, and Take-minakata emerged victorious. The deity worshipped by the Moriya clan was called Mishakuji, a mysterious figure often described as a god of stone, a snake god, or a hunting god, strongly hinting at connections stretching back to the Jomon period. And these characteristics were passed down to the deity of Suwa Grand Shrine.

At the Moriya Museum, the Ontosai ritual was depicted using taxidermied animals. The museum staff kindly provided detailed explanations. It seems that the Suwa faith spread nationwide due to its nature as a god of hunting. As Buddhism spread eating animals was forbidden. However, this was incredibly difficult for people whose livelihood depended on hunting. Suwa Grand Shrine began to issue a kind of indulgence, religiously permitting the consumption of deer. This is how the Suwa faith is said to have spread throughout the country. However, since Suwa Grand Shrine is also sometimes called a god of agriculture, I’m not sure how accurate this account is.

Another interesting point was about the origin of the Ohohri. Although this system has been abolished now, the male child of the Ohohri Suwa family would inherit the position at age eight. For one week, they would seclude themselves in an underground chamber called the “Omuro” to perform a ritual. This ritual involved a stone rod (phallic symbol) and a snake. Then, on New Year’s Day, a week later, the boy, now the Ohohri, would emerge from the chamber, and frogs would be offered. The Moriya clan was responsible for overseeing this series of rituals. It seems that various beliefs have intertwined to form the current Suwa faith.

Behind the Moriya residence, there were small shrines and altars, each also surrounded by small pillars at their four corners. Around them grew Kaji trees, the emblem of Suwa Grand Shrine.

The Moriya Museum building was designed by Terunobu Fujimori, an architect famous for his unique designs, such as the “Flying Mud Boat” and “Takasugi-an” (Too High Tea House).

Shinshu Soba Noodle

After this, I enjoyed some Shinshu soba, a local specialty, before heading to the Suwa Grand Shrine Lower Shrines. Near the soba shop, in the river connected to Lake Suwa, a family of mergansers was swimming.

Suwa Grand Shrine Shimosha

Following the lake road for about 15 minutes, I arrived at Shimomiya Akimiya (Lower Shrine Autumn Shrine). Compared to the Upper Shrine, the buildings here felt grander and newer, giving it the atmosphere of a more modern faith. There’s even a hand-washing basin with hot spring water. And like Izumo Grand Shrine, it has a large Shimenawa (sacred straw rope). While the four Onbashira pillars were present, the shrine had the feel of a modern Japanese Shinto shrine. Although there seemed to be many other sights nearby, I didn’t have much time, so I visited Shimomiya Akimiya and Harumiya (Spring Shrine) before heading home.

There are many places I couldn’t visit this time, such as obsidian excavation sites, Jomon ruins, and other related places and museums associated with Suwa Grand Shrine, so I’d like to visit again when the time is right.

Tokoroten

Tokoroten is a dish made by boiling and then solidifying a type of seaweed called tengusa (Gelidium amansii). When tokoroten is frozen, it becomes kanten, or agar. Suwa’s cold, dry winters are ideal for kanten production, making it the top producing region in Japan. Both tokoroten and kanten are local specialties in Suwa. This time, I had it with a vinegar-soy sauce dressing, but it can also be enjoyed as a dessert with brown sugar syrup.

Two Jomon Museums

Finally, I’d like to introduce two museums where you can see Jomon pottery and dogu, both less than an hour’s drive from the Kawaguchiko area.

The Yamanashi Prefectural Museum of Archeology

Shakado Museum of Jomon Culture

Both are highly recommended museums. You can choose based on your next destination, as they are in different directions.